After an incredibly fast-paced and epic 10-day block, I was ready for a rest day. Thankfully, I was heading to the most rest-inducing parks in the country: Arkansas' Hot Springs National Park.

As the name suggests, the park protects a series of hot springs. Those hot springs had been a huge attraction since the late 19th century. Over time, as people learned about the rejuvenating powers of the pure water, the area became a haven for those with the most leisure time on hand--high society. The bathhouses that cropped up along historic Bathhouse Row weren't content with creating their own style; instead, they tried to emulate the grandeur of the European bathhouses that had been flourishing for quite some time. This led to a local arms race, where neighboring bathhouses competed over who could have the grandest of bathhouses.

But the bathhouses eventually grew out of fashion. Today, the bathhouses are basically historical relics. After Hot Springs became a national park, the NPS sought to preserve the bathhouses for future generations to see, but not to use. The area still had bathhouses--and many people still come here to use them--but they were almost exclusively of the modern-day variety (read: spas). There was, however, one holdover from that bygone era: the Buckstaff Bathhouse. This was the only bathhouse to still provide the "traditional" bathhouse experience that people had experienced over a hundred years ago.

I was determined to try out the traditional bathhouse experience at Buckstaff. But, to my dismay, I learned that it closed at 3 p.m. I'd arrived at 3:30 p.m., so had just missed my chance for the day. I then decided I'd change my plans. Instead of taking today as a rest day, I'd run part of the above-ground trails, and then wake up early the next day and stop by the bathhouse before hitting the road for Little Rock, AR, and Jackson, MS, my next two destinations.

Before setting out for the Sunset Trail, a 17-mile loop around the park, I toured the visitor center, which was in, and had preserved, the old Fordyce Bathhouse. It was funny thinking that this place was state-of-the-art back then. Yet all of the devices and contraptions in each of the rooms seemed utterly outmoded. In fact, some rooms looked more like torture chambers or interrogation rooms than bathing rooms.

The men's bathing area had some remnants of the "grand" era. In the center of the main room was a sculpture, and above it was a beautiful stained glass ceiling. The men's dressing room was nice, too.

Believe it or not, the "electrohydric bath" used to be a thing. It's exactly what it sounds like. As one commentator in 1874 described this treatment, "[t]he current set up between the body of the invalid and the hot water of the bath, must awaken new energies and arouse vitalities." I learned that no one had died from the electrohydric bath, but that bathhouses had at some point stopped giving them.

The tour of the bathhouse was also the first in which I saw the social history, and not merely natural history, that the NPS preserved. The hot springs are a unique and impressive geological feature, but the NPS has done a good job of promoting the way in which we humans have interacted with the springs over time.

I learned that, in their heyday, the bathhouses functioned very much like country clubs. Members of high society would gather here during the fall. And the bathhouses had more than just bath rooms. There were make-up rooms for women, game rooms for men, and sitting rooms where both could socialize.

The gymnasium was fun to see, too. Again, it looked a little bit like a room filled with torture devices and techniques. But really it was just an old-school gym. I envisioned members of the elite sweating away while punching away at the punching bags.

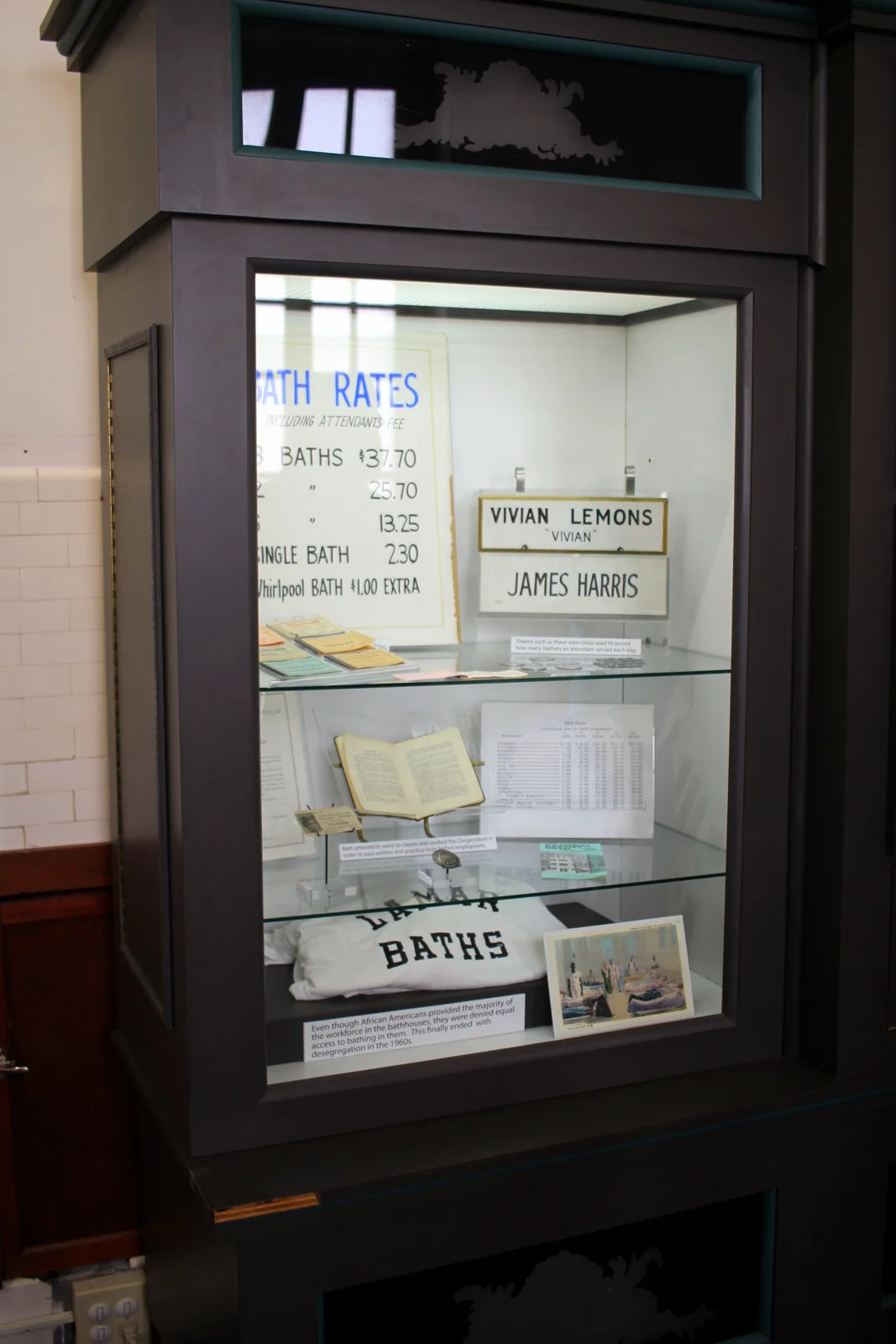

The most compelling exhibit was the one on segregation. The bathhouses of the early 20th century exemplified the cruel reality of Jim Crow America. Practically all of the bathhouse attendants then were African American. Despite the grueling effort they put into bathhouse work, they were not allowed to actually bathe in them. At some point, early African American entrepreneurs created their own black-only bathhouses, including, most notably, the Crystal Bathhouse.

This visit was also important because it helped remind me more generally of the relationship between the natural and human worlds. That is, the national parks are just as much about what we humans have done with land--and to people living on that land--than it is about protecting unique geological features. The visit also reminded me that the NPS has one of the hardest missions possible: to provide enjoyment to the present generation without impairing future generations' ability to enjoy the same.

Having had my fill of learning for the day, I headed out, just before sunset, for the Sunset Trail. I wanted to do an easy run and just get a sense of what the terrain looked like in Arkansas. I ended up doing a 7.5-mile run that wound through a dense forest to an area called Balanced Rock and then to the highest point in the park, Music Mountain. The terrain here was nothing close to epic. Epic America, I'd learned, was far to the west. But it was still soothing to run through forests and on easy dirt trails--both things I'm familiar with as an east coaster.

It was almost dark by the time I finished my run. I'd seen an ad for the Superior Bathhouse Brewery, the world's first--and only--brewery to brew beer using hot springs water. I wasn't about to pass up an opportunity to try beer made with hot springs water, so I headed there for a post-run dinner and drinking session.

It was getting late, and I'd booked an Airbnb with the Barnhardts out in Hot Springs Village, so, after determining that I couldn't notice any difference between beer brewed using hot springs water and beer brewed without using that water, I headed to meet my hosts and call it a night. I'd be up early to get my traditional bathhouse experience.